Forty-three families in rural Texas blend Pentecostal fervor and Anabaptist simplicity.

BY ROGER OLSON, PHOTOS BY DAN BRYANT

FEBRUARY 9, 2005

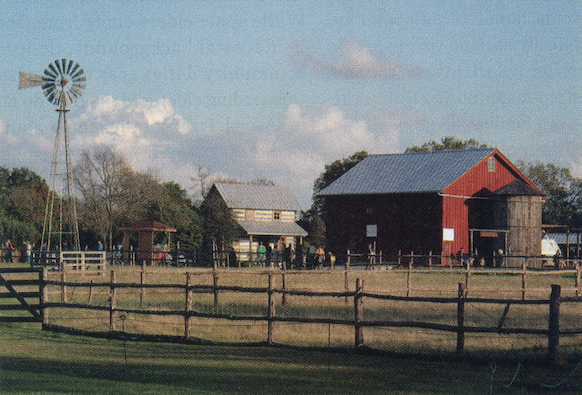

Beginning on the mean streets of Manhattan and migrating to the serenity of the Texas prairie, 43 Christian families are living together in a bold experiment on a 500-acre farm north of Waco, Texas. Many Christians talk about overcoming American individualism through Christian living. But the residents of Homestead Heritage go beyond talk.

This intentional Christian agricultural and crafts community blends Pentecostal fervor with Anabaptist simplicity and accountability. The group is divided into the Brazos de Dios residential community (named after the river that runs through its property) and Homestead Heritage, the umbrella organization under which they do all their work. Brazos de Dios residents are not Amish or even Mennonites, although they have forged close ties with traditional Anabaptists. Rather, they are Christians from many different walks of life engaged together in a modern-day experiment in radical discipleship.

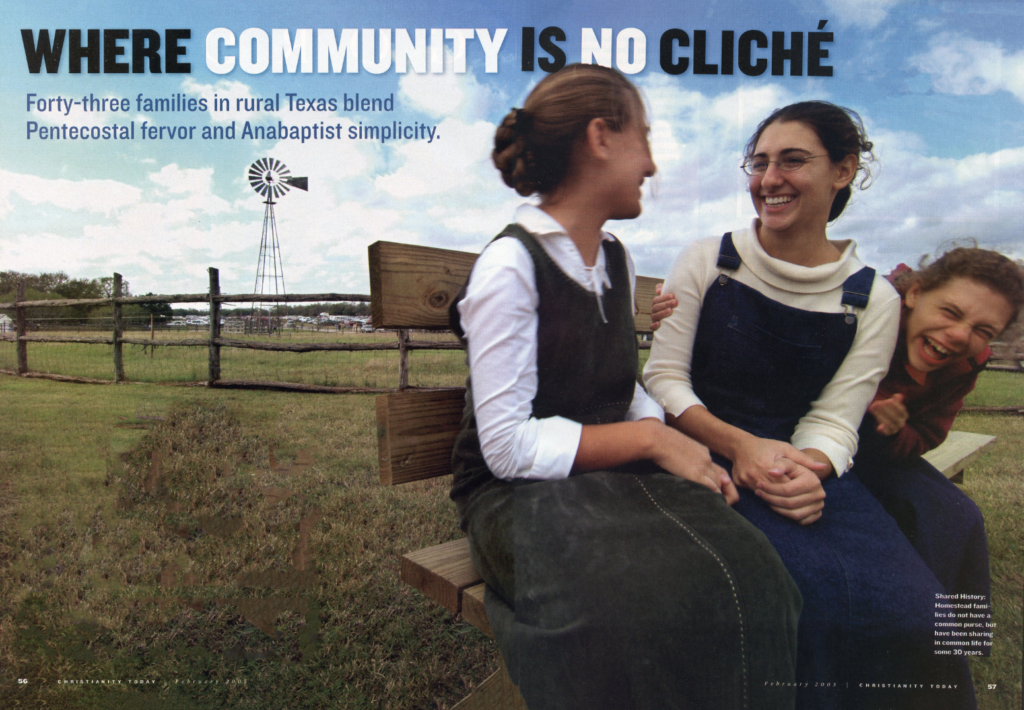

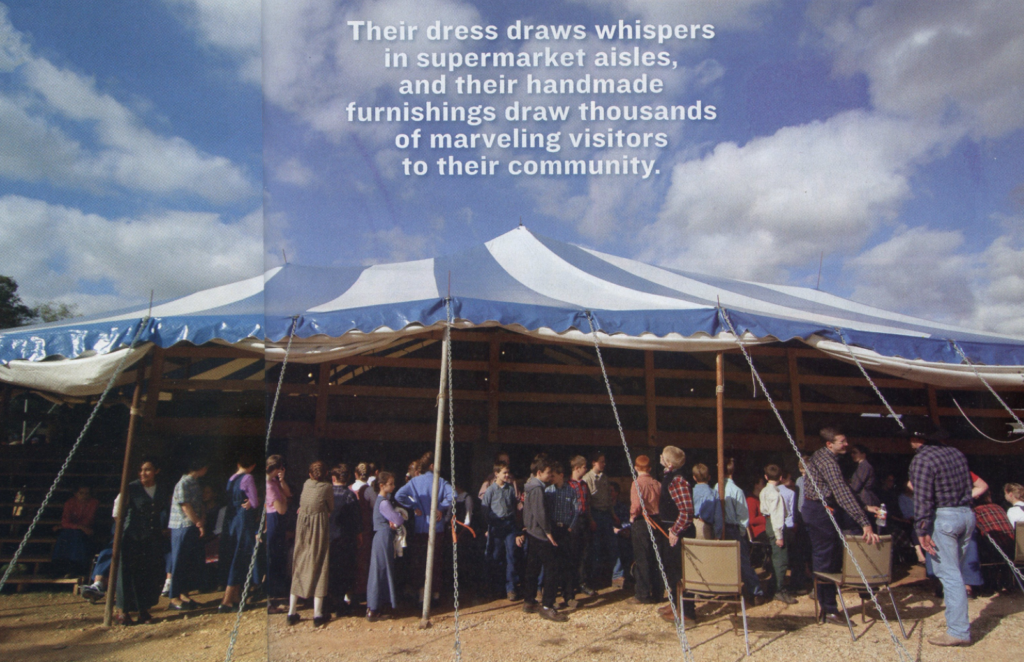

The Homesteaders’ unadorned dress and plain hairstyles draw whispers in supermarket aisles: “They’re from Homestead Heritage.” And their handmade furnishings draw thousands of marveling visitors to their craft village.

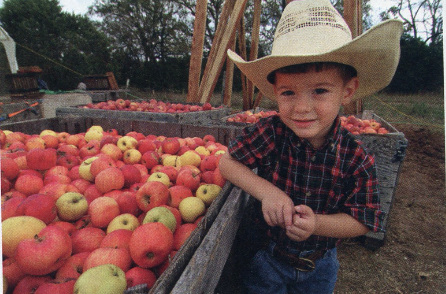

Outsiders also flock to the farm’s festivals every year to experience life as it was 150 years ago: breaking the sod with horse-drawn plows, growing enormous vegetables naturally, grinding grain into flour in an old-fashioned gristmill, making “chocolate” ice cream using carob instead of cocoa.

Not all visitors to Homestead Heritage have a clear idea what lies behind the living-history farm and craft village. With heavenly food, handmade chairs, and gorgeous quilts for sale, some just become loyal customers of Homestead products.

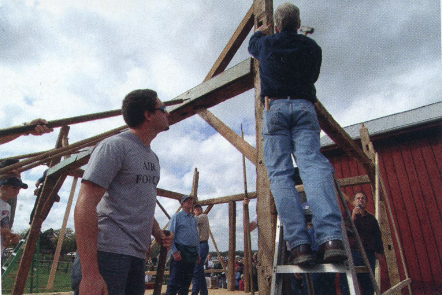

But the biggest crowds at Homestead Heritage turn out for this community’s higher purpose: praising God. Festival-goers typically fill up the seats an hour before a concert begins. A sacred-music concert on Holy Saturday is among the most popular. Performances take place in the community’s enormous sanctuary, hidden among the cedar trees. Like everything else on the land, the Homesteaders themselves built it.

During the event, choral music, accompanied by handmade instruments, fills the sanctuary. The sincerity on the faces of musicians and choristers is unforgettable and tear-streaked faces are common. Testimonies of God’s amazing grace are interspersed with rousing renditions of “There Is a Fountain Filled with Blood” and “Great Is Thy Faithfulness.”

At such events, Homesteaders—including the 900 community members who live on private property near Brazos de Dios—welcome the outside world into their pre-Industrial Revolution world.

Their weekly cell-group services fill up with curious inquirers joining in, but their all-church events, aimed toward community needs, typically have no visitors. They are deeply concerned that their worship not be influenced inappropriately. But the worship style is a familiar blend of classic gospel as well as contemporary choruses. Bible study, testimony, prayers for the sick, and confession of sins all have their place.

Big Apple Beginnings

Homestead Heritage began as an inner-city mission in New York City. In the 1970s and 1980s, it evolved into an experiment in community living, moving to a Colorado farm and then to Texas.

Along the way, changes came about and an Anabaptist influence surfaced. While some elders come from Oneness Pentecostal backgrounds, the present community defies easy categorization. One leading elder told me they do not use the word Trinity in teaching about the Godhead, but in my close questioning I have detected no aberrant teachings about God even though they are reluctant to affirm the language of Nicene orthodoxy. Their impulse is to stick closely to biblical language.

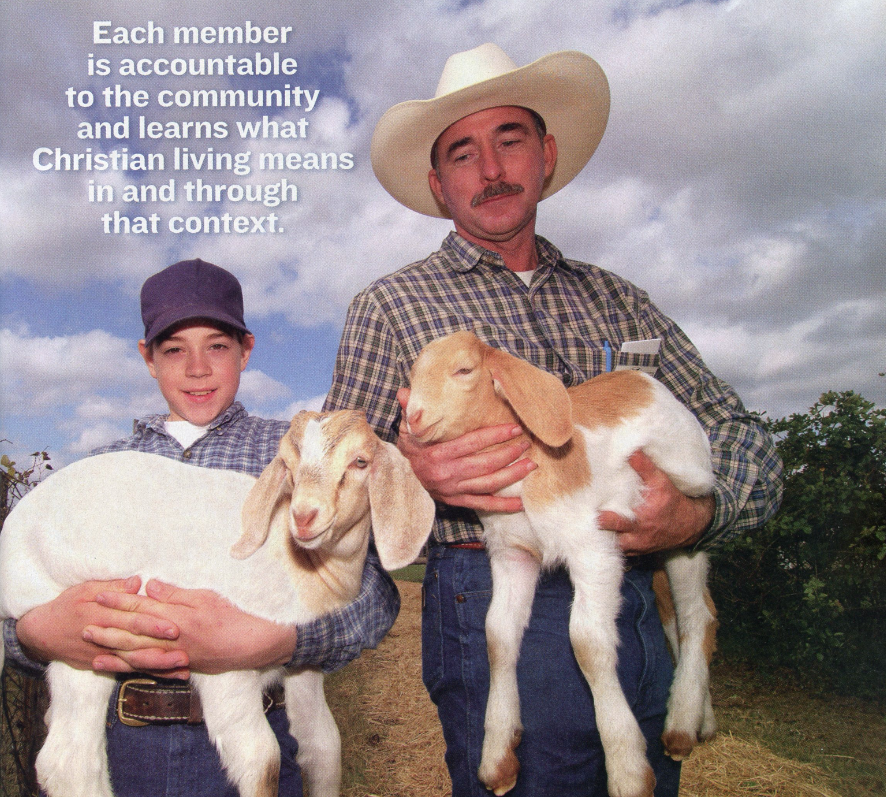

Homestead Heritage theology is generally evangelical but without system or speculation. They choose not to have a creed or a written confession. The focus is on conversion to Christ by faith and self-sacrificial discipleship within the body of Christ. Each member is accountable to the community and learns what Christian living means in and through that context. They love Jesus Christ and worship him as God and Savior.

Rather than produce systematic works of theology, Homestead’s elders are voracious readers and prolific authors, producing home-schooling curricula and other print materials on organic farming, peacemaking, and agrarianism.

Homesteaders emphasize the nuclear family and the rights of parents to raise and educate their children without interference. But they do not reject the world. A philosophy professor, a medical doctor, a lawyer, and an insurance adjustor are among their members. They frequent restaurants and stores. On the other hand, babies are typically born at home, and the sick and elderly die there as well. Prayer and medicine are combined for health and well-being.

The women of Homestead Heritage make their own clothes, often from cloth created on looms in the craft village. They never cut their hair but wear it up in the old-fashioned style often associated with Pentecostals of an earlier era. Most of the men shave and few wear broad-brimmed hats in the Amish style, but their dress is plain and their hair short. Most of the Homesteaders wear no jewelry, including wedding rings.

Use of cosmetics is virtually unknown among them. On the other hand, they own cars and keep in touch with the world by reading numerous publications at their community library. They do not serve on juries, and they register as conscientious objectors to the military. And yet Homesteaders have become well-known, liked, and valued members of the greater community. Members of Homestead Heritage built President Bush’s ranch house near Crawford—only a few miles from Brazos de Dios.

What makes this Christian intentional community tick?

They say it is self-sacrificing love. They make decisions by consensus. Individuals are accountable to the group, but the group exists to serve each individual. They focus much attention on child rearing and practice the idea that “It takes a village to raise a child.” They view themselves as an extended family and call each other “brother” and “sister” regardless of blood relations.

In their view, they share a spiritual DNA provided by Jesus Christ, who is the focus of everything they do. One prospective member (raised in an Israeli kibbutz, but found it disappointing) asked the elders if their lifestyle could be replicated without Jesus. Their answer was a confident No. He joined and found Jesus.

Roger Olson is professor of theology at Truett Seminary, Baylor University, Waco, Texas.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.